This next instalment of the thesis is interesting for several reasons. It is based on the novel by Willi Heinrich, The Willing Flesh. This is a fictionalized rendering of the experiences of Johann Schwerdfeger in the Battle of the Caucasus and the Kuban Pocket.

For someone who is pedantic about weapons in films, this film is probably the best of its time as everything from T 35/85 tanks to small arms both Russian PPSh-41s and German MP40s and MG42s, are the real deal.

James Coburn also makes his second appearance in the thesis after The Great Escape.  Here he is the star, but I am not sure how realistic a nearly fifty-year-old Feldwebel (general equivalent to a sergeant) is. It is essentially a film that deals with the rank and file of the German Army and is derogatory towards all officers.

Here he is the star, but I am not sure how realistic a nearly fifty-year-old Feldwebel (general equivalent to a sergeant) is. It is essentially a film that deals with the rank and file of the German Army and is derogatory towards all officers.

It is also notable that it was a joint German/British production, which could explain some anti-Nazi, anti-war and anti-officer bias in the film. The film did not do well on release in the USA, probably because it came up against Star Wars, but it was successful in Europe and West Germany. Watch Cross of Iron to see why it inspired Quentin Tarantino for Inglorious Bastards.

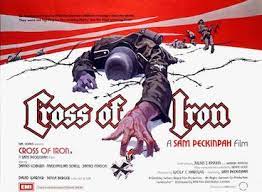

Cross of Iron – 1977

Cross of Iron is the second film of this study to have German lead characters but is remarkably different from its predecessor, The 49th Parallel. Set around the German retreats from the Taman Peninsular during 1942, the film considers the multiple hardships of fighting on the Eastern Front through the eyes of Corporal Steiner (James Coburn), who is later promoted to sergeant, and his close-knit platoon.

The problems for the platoon are exacerbated with the arrival of Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell), an aristocratic officer whose only desire is to earn the Iron Cross. On meeting his new superiors for the first time he encounters their disillusioned bemusement at his desire for service on the Eastern Front.

“Colonel, I would like to make something quite clear… I volunteered for this campaign because I felt that men of quality were needed here. It is time to dispel the myth of Russian invincibility.” Captain Stransky tells them.

“Just how do we do that?” Demands Colonel Brandt.

“Bolstering morale, punishing those who are insubordinate and rebellious. Instilling new respect for ranking officers.”

“Low morale goes hand in hand with defeat after defeat followed by impending defeat. Now you are new to our Russian Front, so I don’t blame you for talking like an… ass.” (This gets a rumble of laughter from the assembled officers, which is cut short by an explosion.

“Of course, I’m not familiar with the Russian Front yet. But I firmly don’t believe that the ideas of the German soldier…”

Brandt harshly interrupts him:

“The German soldier no longer has any ideas! He’s not fighting for the culture of the West… not for one government that he wants: not for the stinking party, he’s fighting for his life. God bless him!”

“Well Sir, I’m a soldier and as a soldier, I think it is my duty to subordinate my ideas to the principles of my country, right or wrong.”

It is this dialogue, at the beginning of the film, that sets the scene for Stransky being the naïve idealist among the jaded veterans of the campaign. His aristocratic heritage forces him to follow ideas of patriotism and his desire for the Iron Cross. He is not a Nazi but is obliged by coincidence to ally himself with Nazi ideals. From the outset, his opinions run against the apathy of his superiors and the insubordination of his antithesis Steiner.

Stransky’s cowering reaction to the explosion in the command bunker reveals his deeper personality more than any of his rhetorical bravado. He is a glory-seeking inexperienced officer who is a coward. The irony goes deeper since characters like Steiner and Brandt are skilled in warfare and have earned the Iron Cross, not through what they regard as acts of bravery but through acts of survival.

Except for Stransky, it is this need for personal survival through the war of annihilation on the Eastern Front that is of paramount importance to Steiner and the rest of his comrades. Steiners’ chances of survival, and those of his men, are put in jeopardy with the arrival of Stransky, who is prepared to risk the lives of others rather than his own.

The problem of Stransky’s cowardice is exposed during the first Russian attack when he claims credit for leading the counterattack, an action designed to earn him the Iron Cross, though, in fact, he was cowering in a bunker.

Lieutenant Meyer, one of Steiner’s comrades, instigated the counterattack but lost his life whilst Steiner himself was injured. Stransky requires testimony from two witnesses; he bribes his adjutant, Lieutenant Trebig, by threatening to disclose his homosexuality and is relying on Steiner’s support. Steiner retorts that he does not believe that Stransky deserves the Iron Cross and when he is called to give testimony, he is reticent to do so.

Lieutenant Meyer, one of Steiner’s comrades, instigated the counterattack but lost his life whilst Steiner himself was injured. Stransky requires testimony from two witnesses; he bribes his adjutant, Lieutenant Trebig, by threatening to disclose his homosexuality and is relying on Steiner’s support. Steiner retorts that he does not believe that Stransky deserves the Iron Cross and when he is called to give testimony, he is reticent to do so.

Cross of Iron contains elements present since the earliest Second World War films. One theme is that war destroys innocence. The film is significant because it is the first film to highlight the young age of people fighting in the war and how their innocence is generally destroyed. This is achieved by the film primarily focusing on the lower echelons of the German Army and specifically the treatment of the young Russian prisoner and Dietz, a new member of Steiner’s squad.

Stransky’s innocence is shattered but the film continues to focus on the young people affected by the war, a factor reiterated during the closing credits. Steiner confronts Stransky and rather than shoot him, he forces him to face a new Russian attack with him. Stransky’s clumsy incompetence makes Steiner burst into hysterical laughter. The laughter continues as the credits begin to roll.

The same patriotic song, sung by boys, from the opening credits, fades but this time the pictures are not of heroic Germany but rather the horrors of the war: civilian hangings, wounded children, and concentration camp inmates. Thus, the anti-war sentiments throughout make Cross of Iron particularly bleak, sentiments which are to a certain extent, replicated in the following film.

So only a few more films left of the thesis. They will be up in the next couple of weeks, the next being The Big Red One.

Keep reading!

Bigt