This is my thesis, sorry/not sorry to go on about it again. I thought I would make it easier rather than harder to access and read by putting it all together. So here it is, the only changes are I’ve removed the numbers showing what ‘chapter’ it would have been in the original blog series.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I hope you take the time to comment and criticise it. I do like a good debate after all.

Over to Orson

The Second World War is the subject matter, more than any other since 1939, that has continued to inspire filmmakers to utilize it as the basis for their films. This is due to a combination of factors succinctly summarized by Harry Lime (Orson Welles) in Graham Greene’s post-war drama, The Third Man in 1949:

“In Italy for thirty years, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo de Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love. They had five hundred years of democracy and peace and what did they produce? The Cuckoo Clock.”

The recent release of Steven Spielberg’s critically acclaimed Saving Private Ryan and several other major Hollywood productions has shown that even at the turn of a new century, filmmakers, audiences, and critics alike are still drawn to the Second World War.

Several significant problems arise in the study of film, especially war films. This study will address a number of these problems ranging from the realistic portrayal of events, the historical value of Second World War films, the treatment of certain taboos and the portrayal of the theme of decency. Many of these factors developed over time; therefore, this study will concentrate on the political, ideological, and cultural reasons behind these developments.

Problems of history and film choice.

John Keegan has described the Second World War as, “the largest single event in human history.” The initial question that, therefore, arises is when the war began and ended. A.J.P. Taylor believed that the Second World War was not a war [in its own right] but rather a continuation of the First World War.

The war affected many nations in many ways, beginning and ending at different times.

For Britain and France, it began in September 1939 with their declaration of war on Germany after the invasion of Poland.

For other European nations, such as Czechoslovakia, it began in 1938 when this nation was annexed.

From a Soviet perspective, The Great Patriotic War [possibly] began with the Russo-Finnish War [Winter War] in late 1939, while in the U.S., their official world war began in December 1941 when Germany declared war on them after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

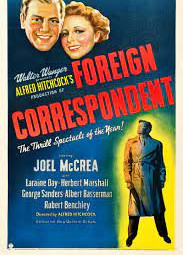

Thus, when choosing films, a chronology between September 1939 and May 1945 was adopted (it also includes a film which transcends the earlier date, Foreign Correspondent, which considers a period just before the war was declared and a short time afterwards).

Big Gun No.2

John Keegan highlights a subsequent problem: “The history of the Second World War has not yet been written. Perhaps in the next century, it will be. Today, though fifty years have elapsed since it ended, the passions it aroused still run too high, the wounds it inflicted still cut too deep and the unresolved problems it left still bulk too large for any one historian to strike an effective balance.”

The same, “passions,” and “unresolved problems,” that pose difficulties for the historian are an ideal arena for a filmmaker, as shown by the correspondingly large number of Second World War films, but the plethora of material poses a problem for an MA study, a situation remedied only by imposing criteria to reduce the number to a manageable level.

The length of this study has dictated that no more than fourteen films were chosen. The initial criterion was that only United States and Great Britain films would be used. This meant that only English-language films were utilized. The following criterion was the sphere of operations that would be included. It was decided to focus on films dealing with the war in Europe, North Africa, and the North [and South] Atlantic, which was a distinct conflict in many ways from the Pacific War.

Factors for consideration in the study of war film.

William Friedkin, the director of The Exorcist has:

“Always believed that film should be an emotional experience, it should make you laugh or cry or be scared, but it should also inspire and provoke you and make you reflect.”

The filmmaker must work hard to stimulate the viewers’ emotions to make them forget their comfortable surroundings. The film has, therefore, to appeal to the sensibilities of as many of the cinema audience as possible. Therefore, as the population has changed since the late 1930s, so have the methods that filmmakers have adopted to appeal to the masses.

Keegan’s ‘passions’ and ‘unresolved problems’ that have led to so many Second World War films immediately provide many of Friedkin’s ingredients, so the filmmaker has a head start. In relation to the theme of war represented in such films, the situation is more complicated with a multitude of factors affecting the representation of the theme.

Realism?

Realism is the most complicated factor. In the fantasy world of feature films, it is an abstract concept. The relative comfort of the viewer creates an atmosphere whereby attaining total empathy is impossible. Surrounded either by the comfort of home with an arbitrary ability to start and stop the film as they desire or in a warm, dark auditorium surrounded by hundreds of people eating popcorn inhibits the levels of reality achieved in the film viewing situation. However, this has not stopped filmmakers from utilizing every possible technological and dramatic process to produce as much realism as possible.

The subject of realism itself can be broken down into various linked categories. The most important factor, from a historical perspective, is the realistic portrayal of actual events. Another would be the realistic representation of the motivations and emotions of the characters but most importantly for the purposes of this study, the realistic portrayal of the theme of decency.

It is the representation of this theme that has appeared to change and develop most in the sixty-year period considered in this study. In this way, the question considered is whether the stereotypical character representations of earlier films are more realistic than those of later films and if this is or is not the case, what factors have led to this change.

Heroism

A key factor in relation to character representations that is important is the portrayal of heroes and what is deemed heroic. There are films within this study that undoubtedly glorify the pursuit of war and those that pursue it portraying great commanders such as Rommel and Patton as heroes and portraying great battles such as D-Day and The Battle of Britain as heroic. These representations tend to appear only in the pre-1970 era. Since then, the onus has shifted to less significant characters, such as previously unnamed lower ranks. This focus on the lower echelons of the military establishment and not the large-scale battles highlights more personable stories and that military action was often a battle for survival, not success against the enemy. This is clearly a progression from larger-than-life stories to everyday characters in the essentially civilian armies that find themselves reacting to the demands and stresses of war.

These representations tend to appear only in the pre-1970 era. Since then, the onus has shifted to less significant characters, such as previously unnamed lower ranks. This focus on the lower echelons of the military establishment and not the large-scale battles highlights more personable stories and that military action was often a battle for survival, not success against the enemy. This is clearly a progression from larger-than-life stories to everyday characters in the essentially civilian armies that find themselves reacting to the demands and stresses of war.

Changing Attitudes

Changes in attitudes in the Western World since the 1930s have affected the portrayal of certain themes in relation to war films. The xenophobic anti-German rhetoric of earlier films does not inspire modern filmgoers in the way it influenced their parents or grandparents. This younger generation has grown up with few anti-German animosities most especially in the United States, which dominates the war film genre post-1970. This study will highlight the changing portrayal of German and Allied characters. The move from the stereotypical comic book, goose-stepping, rhetoric-fuelled character towards a more balanced interpretation can be seen in films such as Cross of Iron, highlighting an army disillusioned with their leaders and war-mongering policies. None of the films selected defend atrocities perpetrated by the Nazi regime but instead show that most of both Allied and Axis soldiers were young men confronting the same horrors of war and desire to survive. In conjunction with increasingly sophisticated German characters in war films, a fuller treatment of certain ethical, moral, or political taboos that arise from dealing with such a diverse and emotional subject as war is considered.

None of the films selected defend atrocities perpetrated by the Nazi regime but instead show that most of both Allied and Axis soldiers were young men confronting the same horrors of war and desire to survive. In conjunction with increasingly sophisticated German characters in war films, a fuller treatment of certain ethical, moral, or political taboos that arise from dealing with such a diverse and emotional subject as war is considered.

Aliens vs Dinosaurs

This is the second part of the William Friedkin section and focuses on the more heavyweight considerations of censorship relating to violence and the treatment of the Holocaust in feature films. Ironically, it also deals with whether films could be viable educational tools for learning history. At the time of writing the thesis, I had no desire whatsoever to be a teacher but, several years later, when I did become a history teacher, I used feature films wherever possible. Steven Spielberg is discussed here too; he is the only director in the thesis who has two films considered. The title Aliens vs. Dinosaurs comes from the discussion of the subject matter of two of his greatest hits that do not involve the Second World War. Little did I know at the time how Spielberg’s films and series would dominate this arena to this day and also lead to a resurgence in Second World War productions on both the big screen and the small.

Steven Spielberg is discussed here too; he is the only director in the thesis who has two films considered. The title Aliens vs. Dinosaurs comes from the discussion of the subject matter of two of his greatest hits that do not involve the Second World War. Little did I know at the time how Spielberg’s films and series would dominate this arena to this day and also lead to a resurgence in Second World War productions on both the big screen and the small.

Censorship

Most censorship of film was by governmental bodies such as the Hays Commission in the United States, which was: “a self-regulatory body, [which]had a list of eleven [expletive] ‘don’ts’ and twenty-five ‘be-carefuls’. These guidelines were also known as the Motion Picture Production Code and lasted until the 1960s.” In Britain, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) established in 1913 acts as a censor, the board’s decision is final and there is no means of appeal. In this study, this board has the most tremendous significance because all films viewed have been the British-released versions while all, but Saving Private Ryan were viewed on video.

In Britain, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) established in 1913 acts as a censor, the board’s decision is final and there is no means of appeal. In this study, this board has the most tremendous significance because all films viewed have been the British-released versions while all, but Saving Private Ryan were viewed on video.

Violence

“Since the early 1900s, violence has been the most controversial and emotive aspect of the movies.” The earlier period of films considered here made between 1939 and 1969 was potentially seen by audiences that had experienced the horrors of the war first-hand, therefore, it was possibly deemed tasteless for filmmakers to highlight such scenes.

The prevalent sentiments in films of this period were those of good feeling and pride of achievement in having beaten the Germans, which continued the theme of pro-war propaganda films synonymous with the war years.

The move away from such sentiments was due to several factors that arose in the 1960s and 1970s such as the emergence of television. Television, with its ability to bring almost real-time reportage into peoples’ living rooms, meant that the real horrors of the Vietnam War were widely viewed.

Censorship of such material was less than in the Second World War and reports from battles were common. John Trevelyan, who was secretary of the BBFC between 1958 and 1971 having joined the board in 1951, said:

“If there was enough of it [screen violence, then it will] desensitize people so that they find violence both normal and acceptable.” The increase of explicit violence, much of it gratuitous, rapidly transferred from reportage of the Vietnam War to fantasy on the big screen. This trend began in the early 1960s and continued through the 1970s and the 1980s with films starring heroes such as Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger with ever-increasing body counts. In conjunction with better technology allowing more realistic film effects, war filmmakers have subsequently re-enacted most life-like situations, such as explosions and injuries. The advancement is most noticeable in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan in 1988.

This trend began in the early 1960s and continued through the 1970s and the 1980s with films starring heroes such as Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger with ever-increasing body counts. In conjunction with better technology allowing more realistic film effects, war filmmakers have subsequently re-enacted most life-like situations, such as explosions and injuries. The advancement is most noticeable in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan in 1988.

The Holocaust

The Holocaust arguably presents filmmakers with the most difficulty. The horrific events were eventually [there had been others but not portrayed in this way] portrayed by a major Hollywood film in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List in 1993. Despite its horrific subject matter, it achieved both commercial success and critical acclaim. The use of stark black and white film portrayed events in the film with even more emotion.

Despite its horrific subject matter, it achieved both commercial success and critical acclaim. The use of stark black and white film portrayed events in the film with even more emotion.

Educational Tool

Schindler’s List also requires comments on whether there is any value in war films being used as an educational tool and whether filmmakers have sought to utilize their films in this role. The problems in using film in this way are many. Films are dramatized depictions of true or completely fabricated stories with facts excluded or exaggerated to create a more exciting story.

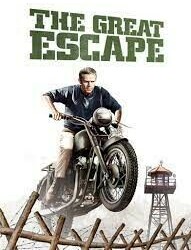

This point is highlighted during the opening credits of the Great Escape in 1963: “This is a true story/ Although the characters are composites of real men, and time and place have been compressed, every detail of the escape is as it really happened.” Here the filmmaker admits a true story has been adapted to suit the demands of a feature film. Stereotypical German attributes were undoubtedly utilized in propaganda films of the war and immediately post-war years.

Any discussion of historical facts in relation to the educational value of war films returns to earlier discussions of realism. Realistic portrayals of, for example, action sequences, in conjunction with the use of computers, bridge the gap between documentary newsreels and feature films to a greater extent than ever before.

Special effects can create more realistic wounds, explosions, and bullet strikes, such as in Saving Private Ryan. However, though war films have become more realistic in some ways, it must be remembered by both the viewer and the filmmaker that the world of feature films is one of fantasy.

Feature films are influential in developing peoples’ beliefs, but the filmmaker has limited influence over what the viewer deems as fantasy or reality. Therefore, the viability of utilizing feature films as an educational tool is filled with difficulties.

The tensions between educational and fantasy films are further highlighted by the fact that Steven Spielberg, who directed Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan also directed ET: The Extra-Terrestrial, the most successful children’s fantasy film of all time [at the time of writing] as well as Jurassic Park and Jaws. Therefore, this study will consider the educational aspects, if any, of the films included.

Therefore, this study will consider the educational aspects, if any, of the films included.

Foreign Correspondent Movie Review

I quickly realised that I do not want to discuss just books or even just books that have been made into films. I am interested in most things to do with the Second World War and films are an important part of that. Therefore, I am also going to have a section of the website where other media forms are dealt with.

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) Foreign Correspondent is one such example. I discussed the film in my MA Thesis, and this is an edited version of what I wrote and believed twenty years ago, so things might have changed now. The text in italics is from the original thesis.

My Opening Thoughts

‘Since its first development celluloid has been a method of manipulating people’s feelings and beliefs. It has been used as a propaganda tool, especially in times of war, a specific example being Laurence Olivier’s Henry V in 1944. As war is a fervent stimulator of nationalism war films are important in stimulating and reflecting such nationalism.

The Plot

The earliest film considered here; Foreign Correspondent produced in 1940 and directed by Alfred Hitchcock, is a film that initially highlights the use of film as propaganda. It begins with Mr Powers (Harry Davenport), the editor of the Daily Globe, deciding that as: ‘There is a crime happening on that bedevilled continent [Europe], that he needs a crime reporter rather than a foreign correspondent to deal with the story.

His choice is John Jones (Joel McCrea) who uses the pen name Huntley Haverstock, a maverick crime reporter but naïve of the European situation. He sends him to London to interview the Dutch politician Van Meer (Albert Basserman) who is one of the signatories of an international peace agreement. The agreement contains a secret clause that anyone wishing to bring about a war will know.

On his arrival, Haverstock immediately becomes embroiled in the events that are plunging Europe towards war when he witnesses the assassination of Van Meer and takes it upon himself to follow the assassin. He discovers an intricate plot with assassins and spies who have kidnapped Van Meer and replaced him with a doppelganger.

They subsequently assassinate the imposter in the hope that the real Van Meer will reveal the contents of the secret clause. The conspiracy is led by Stephen Fisher (Herbert Marshall) who is using his position as the head of a peace organisation as a front for his real activities. Haverstock is immediately attracted to Fisher’s daughter, Carol (Laraine Day) thus becoming more deeply involved with the unfolding events. Van Meer is eventually rescued unconscious, but it is too late, the war has begun.

The Plot Thickens

Fisher, realising that he has been discovered, takes his daughter, and flees to America. The unconscious Van Meer has been unable to damn Fisher with the evidence against him so Haverstock and his British companion, Scott ffolliot (George Sanders) board the same flying boat as Fisher. On board, they await a cable that will inform them that Van Meer has regained consciousness and has revealed his torture and that Fisher will be arrested when they land. Unfortunately, a German warship shoots them down. They survive, are picked up by a US ship and Haverstock manages to get his story through to Mr Powers.

What I thought back then

This classic Hitchcockian thriller is important because America, the nation that produced it, was not actually at war in 1940 when the film was released. At this time, the prevalent American opinion was that of continued isolationism from another war in Europe.

Against this political backdrop, Foreign Correspondent is notable because of certain stereotypical implications that are represented in the film. The German characters are portrayed as inherently evil and are not averse to torturing and murdering innocent civilians. These anti-German stereotypes are significant because the film highlights the attempt to convince a sceptical nation that the German nation was not to be trusted. This attempt is further highlighted in Foreign Correspondent because it is undoubtedly a call for America to come to the aid of the subjugated Europeans, a fact highlighted most clearly in the final scene as Haverstock is broadcasting from America from a radio station in Britain.

“Hello America, I’ve been watching a part of the world being blown to pieces, a part of the world as nice as Vermont, Ohio, Virginia, California, and Illinois lies ripped up and bleeding like a steer in a slaughterhouse. And I’ve seen things that make the history of the savages read like the Pollyanna legends.”

The strong anti-German sentiment is combined with an implied Anglo-American unity underlined by the sound of bombing threatening to interrupt the broadcast as the scene fades into the Star-Spangled Banner. At first, Haverstock’s character epitomised the American people and their view of the European situation at this time. Initially, he is naïve about the conflict in Europe but becomes deeply embroiled realising that America should be involved militarily.

Just as Haverstock epitomises [the majority of] the American population, Fisher is used to represent the evil deeds of the Nazis. This is symbolised most prominently when Fisher is present at Van Meer’s torture. The captive then calls for someone to come to the aid of Europe and denounces his captors thus:

“I see there is no help, no help for the suffering world. You… You cry peace Fisher. Peace when there was no peace, only war and death. You’re a liar Fisher, a cruel, cruel liar. You can do what you want with me, that’s not important, but you’ll never conquer them, Fisher. Little people everywhere… Lie to them, drive them, whip them, force them into war when the beasts like you will devour each other. The world will belong to the little people.”

Final Thoughts

The other nations of Europe, particularly Britain and Holland [the Netherlands] are characterised as peace-loving innocents evilly threatened by war-mongering Germany. Scott ffolliot is a stereotypical eccentric British aristocrat whilst Haverstock believes that to fit in, he had better wear a bowler hat and carry an umbrella. Haverstock is the archetypal brash, outgoing American character that outfoxes both the evil Germans and the bumbling peace-loving British and Dutch. Above all, the hero, Haverstock, is thoroughly decent and infallible. The paternalistic theme developed here is that the nations of Europe being attacked by Germany were incapable of fending for themselves without help from America. The film is therefore significant because various methods are used to portray a particular message, setting a precedent that continued for more than thirty years.’

Foreign Correspondent Movie Review

I quickly realised that I do not want to discuss just books or even just books that have been made into films. I am interested in most things to do with the Second World War and films are an important part of that. Therefore, I am also going to have a section of the website where other media forms are dealt with.

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) Foreign Correspondent is one such example. I discussed the film in my MA Thesis, and this is an edited version of what I wrote and believed twenty years ago, so things might have changed now. The text in italics is from the original thesis.

My Opening Thoughts

‘Since its first development celluloid has been a method of manipulating people’s feelings and beliefs. It has been used as a propaganda tool, especially in times of war, a specific example being Laurence Olivier’s Henry V in 1944. As war is a fervent stimulator of nationalism war films are important in stimulating and reflecting such nationalism.

The Plot

The earliest film considered here; Foreign Correspondent produced in 1940 and directed by Alfred Hitchcock, is a film that initially highlights the use of film as propaganda. It begins with Mr Powers (Harry Davenport), the editor of the Daily Globe, deciding that as: ‘There is a crime happening on that bedevilled continent [Europe], that he needs a crime reporter rather than a foreign correspondent to deal with the story.

His choice is John Jones (Joel McCrea) who uses the pen name Huntley Haverstock, a maverick crime reporter but naïve of the European situation. He sends him to London to interview the Dutch politician Van Meer (Albert Basserman) who is one of the signatories of an international peace agreement. The agreement contains a secret clause that anyone wishing to bring about a war will know.

On his arrival, Haverstock immediately becomes embroiled in the events that are plunging Europe towards war when he witnesses the assassination of Van Meer and takes it upon himself to follow the assassin. He discovers an intricate plot with assassins and spies who have kidnapped Van Meer and replaced him with a doppelganger.

They subsequently assassinate the imposter in the hope that the real Van Meer will reveal the contents of the secret clause. The conspiracy is led by Stephen Fisher (Herbert Marshall) who is using his position as the head of a peace organisation as a front for his real activities. Haverstock is immediately attracted to Fisher’s daughter, Carol (Laraine Day) thus becoming more deeply involved with the unfolding events. Van Meer is eventually rescued unconscious, but it is too late, the war has begun.

The Plot Thickens

Fisher, realising that he has been discovered, takes his daughter, and flees to America. The unconscious Van Meer has been unable to damn Fisher with the evidence against him so Haverstock and his British companion, Scott ffolliot (George Sanders) board the same flying boat as Fisher. On board, they await a cable that will inform them that Van Meer has regained consciousness and has revealed his torture and that Fisher will be arrested when they land. Unfortunately, a German warship shoots them down. They survive, are picked up by a US ship and Haverstock manages to get his story through to Mr Powers.

What I thought back then

This classic Hitchcockian thriller is important because America, the nation that produced it, was not actually at war in 1940 when the film was released. At this time, the prevalent American opinion was that of continued isolationism from another war in Europe.

Against this political backdrop, Foreign Correspondent is notable because of certain stereotypical implications that are represented in the film. The German characters are portrayed as inherently evil and are not averse to torturing and murdering innocent civilians. These anti-German stereotypes are significant because the film highlights the attempt to convince a sceptical nation that the German nation was not to be trusted. This attempt is further highlighted in Foreign Correspondent because it is undoubtedly a call for America to come to the aid of the subjugated Europeans, a fact highlighted most clearly in the final scene as Haverstock is broadcasting from America from a radio station in Britain.

“Hello America, I’ve been watching a part of the world being blown to pieces, a part of the world as nice as Vermont, Ohio, Virginia, California, and Illinois lies ripped up and bleeding like a steer in a slaughterhouse. And I’ve seen things that make the history of the savages read like the Pollyanna legends.”

The strong anti-German sentiment is combined with an implied Anglo-American unity underlined by the sound of bombing threatening to interrupt the broadcast as the scene fades into the Star-Spangled Banner. At first, Haverstock’s character epitomised the American people and their view of the European situation at this time. Initially, he is naïve about the conflict in Europe but becomes deeply embroiled realising that America should be involved militarily.

Just as Haverstock epitomises [the majority of] the American population, Fisher is used to represent the evil deeds of the Nazis. This is symbolised most prominently when Fisher is present at Van Meer’s torture. The captive then calls for someone to come to the aid of Europe and denounces his captors thus:

“I see there is no help, no help for the suffering world. You… You cry peace Fisher. Peace when there was no peace, only war and death. You’re a liar Fisher, a cruel, cruel liar. You can do what you want with me, that’s not important, but you’ll never conquer them, Fisher. Little people everywhere… Lie to them, drive them, whip them, force them into war when the beasts like you will devour each other. The world will belong to the little people.”

Final Thoughts

The other nations of Europe, particularly Britain and Holland [the Netherlands] are characterised as peace-loving innocents evilly threatened by war-mongering Germany. Scott ffolliot is a stereotypical eccentric British aristocrat whilst Haverstock believes that to fit in, he had better wear a bowler hat and carry an umbrella. Haverstock is the archetypal brash, outgoing American character that outfoxes both the evil Germans and the bumbling peace-loving British and Dutch. Above all, the hero, Haverstock, is thoroughly decent and infallible. The paternalistic theme developed here is that the nations of Europe being attacked by Germany were incapable of fending for themselves without help from America. The film is therefore significant because various methods are used to portray a particular message, setting a precedent that continued for more than thirty years.’

Great Sunday Movie

One of the great Sunday movies, The Dam Busters was undoubtedly one of the first war films I watched as a child, and it was probably shown on a Sunday afternoon or in the Christmas holidays. The Dam Busters’ music, specifically the Dam Busters’ March is known by many. The music itself has become part of British culture as it is often ‘sung’ at football matches.

The raid itself has become a trope in other films, probably most noticeably with the attack on the Death Star in Star Wars but also an advert for a certain beer where a German guard drank some beer and then caught the bouncing bombs as if he was a goalkeeper.

The film is based on two books

These are (As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) The Dam Busters by Paul Birkhill and Enemy Coast Ahead by Guy Gibson who was awarded the Victoria Cross for leading this mission. There have been many other books and documentaries, and a potential remake by Peter Jackson has been rumoured for years. We shall see if that actually materialises. In this, the 80th anniversary of the operation, it’s worth another watch.

The Dam Busters 1955

‘The Dam Busters is the first film in this study to portray a true event from the Second World War and it concerns the development and use of the bouncing bomb in Operation Chastise. The story begins in 1942 with inventor Barnes Wallace (Leslie Howard) attempting to develop an idea for a new kind of bomb. The targets for the bomb, once developed, were the large dams providing water for the industries of the Ruhr region of Germany.

Wallace’s stubborn devotion and self-belief in his radical idea initially force him to fight his bureaucratic superiors and their red tape to get support for his plan. Eventually, he succeeds, and the raid is set in motion with the creation of 617 Squadron, led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson (Richard Todd).

The story then follows the final development of the bomb and the training of the new squadron. Both parts of the task encounter various setbacks in the short run-up to the raid. During testing, the bomb keeps breaking up as it hits the water. The squadron, whilst practising low flying, discovers the difficulty of flying at the right altitude to drop the bomb at night at the right distance away to reach the dam at the right part of the bounce.

Two of the dams, the Möhne and Eder Dams were destroyed and the Sorpe was lightly damaged. However, when Wallace finds out, he is immediately struck with grief because of the bomber’s losses. Up until this time, the problem of destroying the dams had manifested itself only on an academic level. He had not considered the possible losses. When the reality of the human losses becomes evident such naivety is destroyed but Gibson reminds Wallace, “If all those fellows had known from the beginning that they would not be coming back, they’d have gone for it just the same. There isn’t a single one of them would have dropped out. I knew all of them, I know it’s true.”

The psychological cost

Wallace’s heroic credentials are on the verge of being destroyed but Gibson is able to restore his faith and the ensuing credits enable the audience to maintain the feeling of achievement avoiding any major consideration of the morality or military necessity of the raid.

Therefore, The Dambusters maintains the wartime theme that every Allied mission was right and decent despite the post-war historical debate about whether the riad caused damage to the German war effort. However, there are two factors where the film is significant. The first is the film’s use of technology and the second is the character representation and political influences of the time. Certain aspects of the film highlight the limits of technology at the time of its production. The most notable example, which adversely affects the realism of the film, is when the bombs explode and cause plumes of water, which are clearly superimposed. Though to balance this technically weak footage, scenes of actual test drops [though edited] are used earlier in the film.

How does it fit with the other films?

Its production in 1955 shows a continuation of nationalistic ideals that had been promoted in wartime. Though there are no German characters to directly compare with the heroic British civil and military personnel. Produced after the Korean War and in the first years of the Cold War, Soviet Russia was the new enemy and West Germany was now an ally. Thus, the earlier films highlighting Germany as the manifestation of evil are already dated. The destruction of the dams is more important than killing Germans. The film is therefore pro-British rather than anti-German.’

The Longest Day Film 1962 (viii)

This is the first of Cornelius Ryan’s epic histories to be transferred to the big screen. The Longest Day film from 1962 makes a valiant attempt to deal with the extraordinary scope of Operation Overlord, The D-Day Landings. As well as using Ryan as the scriptwriter filmmakers used several participants from the battle.

My favourite anecdote of the many that are associated with the making of the film, is that Richard Todd, playing Major Howard, had actually been one of the Parachute Regiment soldiers who helped reinforce Howard’s coup de main force at the bridges.

During the actual battle, Todd relayed information to Howard. This is shown in the film, so technically Todd delivered himself a message. During filming, Todd wore the beret he had worn during the battle, the only difference was a change in cap badge from his original Parachute Regiment wings to the Badge of Howard’s Ox and Bucks.

Synopsis of the film

The Longest Day takes such pro-allied compassions further. Based upon the book written by Cornelius Ryan this film chronologies the largest [amphibious] invasion of all time., the D-Day landings of 6th June 1944. The story begins just prior to the invasion and visits the numerous characters of all ranks at their various military establishments both in France and in Britain as they prepare for the forthcoming battle.

The Seventh Virgin Film Guide has called The Longest Day: “One of the most ambitious films undertaken… [The director] Darryl Zanuck, who spared no expense bringing The Longest Day breath-taking scope and authenticity, going so far as to insist that shooting be done only in conditions that matched those of the actual event… The Longest Day is visually stunning- its extraordinary camera movement and Cinemascope photography brilliantly augmenting the meticulously re-enacted battle scenes… this magnificent film was the most expensive black and white production to its date.”

Why is it called The Longest Day – supposedly?

To emphasise the epic nature of the film Zanuck included various speeches by notable commanders from both sides. In the opening scene, whilst overseeing the defensive preparations, Rommel (Werner Hinz) says to his companions:

“How calm and peaceful it is. A strip of water between England and the continent… between the Allies and us. But beyond that peaceful horizon, a monster waits. A coiled spring of men, ships, and planes… straining to be released against us. But not a single invasion may come, gentlemen, I shall destroy the enemy there, at the water’s edge. The first twenty-four hours will be decisive. For the Allies and us, it will be the longest day… the longest day.”

It is around this phrase that the film revolves, a similar theme adopted with a later film adaption of a subsequent Cornelius Ryan book, A Bridge Too Far. John Wayne’s character, Colonel Vandervoort of the American 82nd Airborne Division continues the sentiments begun by Rommel as he encourages his men prior to their take off with the almost Churchillian speech: “We are on the threshold of the most crucial day of our lives.

How realistic is it?

As with many of the films of this earlier era, the action sequences often seem stilted. Many of the scenes in the film seem particularly choreographed; there is no feeling of the real chaos and disorder that soldiers encountered on the day of the feelings which Steven Spielberg tries to convey in 1998’s Saving Private Ryan. As a result, the film lacks realism.

The film’s major premise was not the realistic portrayal of the invasion but rather a proclamation of the glory of such a historically significant event. The story does not delve too deeply into the personalities of the numerous characters involved and their personal battles but concentrates on the grand overview. The sheer scale of the film does not allow such in-depth studies.

The film essentially glorifies the battle by not dwelling overly much on chaos, injury or death. In this way, the film attempts to glorify the achievements of Operation Overlord. Since the film concentrates on the large scale of the battle, many of the major characters in it are the directors of the events themselves, the high-ranking officers. Any inclusion of lower ranks is ironically portrayed in a light-hearted manner so as not to bring the viewer away from the true seriousness of war.

How does it fit with other films?

The Longest Day maintains, to a certain extent, the various racial stereotypes found in the earliest Second World War propaganda films such as The 49th Parallel. The British are stoically stiff-upper-lipped, and the Americans are brashly boyish. The film has been criticised as treating the German characters much more sympathetically than they had in earlier films, the way that this is achieved is by refusing to taint every German character with Nazism, but they are still depicted as being arrogantly confident.

The 2000 Film and Video Guide called The Longest Day, “one of the last great epic World War II films.” In agreement with this, there has been no film since which has dealt with the great extent of the battle on such a scale. Zanuck went to pedantic lengths like Spielberg would go to over thirty years later with his two epic Second World War films.

Amongst its contemporaries in this earlier period, the film was undoubtedly the epic that Matlin [editor of the 2000 Film and Video Guide] contends but at the turn of the twenty-first century, it seems to lack the graphic authenticity of later films, films that no longer want to glorify the pursuit of war.

The era in which the film was produced is re-iterated by the maintenance of nationalistic stereotypes that are included within it, even if they are slightly more sympathetic in dealing with the enemy. Germany, the old enemy, by 1962, had been rebuilt and included within NATO which includes many of its former enemies, to face the current enemy, the Soviet Union.

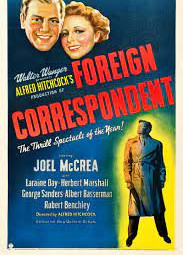

Steve McQueen Motorbike Movie

As quiz questions go, asking about Second World War films with Steve McQueen and a motorbike in, would not be that challenging for many people. The Cooler Kings’ attempts to jump his stolen ‘German motorbike’ (more of this later) into Switzerland is arguably the most remembered scene from The Great Escape. Spoiler alert, he fails and is sent back to Stalag Luft III. Used as a trope in many other films and with many other quotable and memorable scenes.

This is another classic Sunday film riddled with stars of the time such as James Garner as ‘The Scrounger’ and Richard Attenborough as ‘Big X’. Just as riddled with historical inaccuracies, some like Steve McQueen and the Motorbike are entirely made up, while others, such as the amalgamation of several real people into single characters or changing their nationality are there so they could be played by Hollywood stars and get bums on cinema seats.

are entirely made up, while others, such as the amalgamation of several real people into single characters or changing their nationality are there so they could be played by Hollywood stars and get bums on cinema seats.

It is a book too

The film is based on the book of the same name by (As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) Paul Brickhill, who was a Prisoner of War at the camp. The Great Escape tunnel names, Tom, Dick and Harry were built three prisoners made a ‘home run’ and many more were executed, this film is truly a gateway for many of a certain generation(s) into the Second World War. The poster could almost have been Steve McQueen, the motorbike, and the Great Escape and been none the worse for it.

What did I think?

This is another classic story from The Second World War like The Dambusters. The film considers the efforts, of Air Force officers from various Allied nations, as they plan and mount an escape from a new maximum-security prisoner-of-war camp. The camp is in Germany [now Poland] and was specially constructed to house these men because they had all mounted numerous escape attempts from other camps. As the new camp commandant, Colonel von Luger (Hannes Messemer) puts it, “All our rotten eggs are in one basket.”

The German authorities, especially the Gestapo and SS, are suspicious that there is an organised network among the officers, but it becomes immediately apparent that the organisation, codenamed ‘X’ is larger and better organised than they had envisioned.

Headed by Major Bartlett (Richard Attenborough) codenamed ‘Big X’. They immediately set about planning the largest mass escape ever. This is one of the most famous Second World War films and is split into two distinct sections. The former is the planning of the escape and the digging of the tunnels, the latter is the escape itself.

It is a typical heroic story that highlights stereotypical characters with the prisoners stoically determined to fight the Germans from captivity.

It was their duty?

A policy outlined by Group Commander Ramsey (James Donald) when he informs Luger that:

“It is the sworn duty of all officers to try and escape, if they can’t, it is their sworn duty to cause the enemy to use an inordinate number of troops to guard them and their sworn duty to harass the enemy to the best of their ability.”

The story depicting a heroically famous deed is relatively simple and takes on a typically ‘Boy’s Own’ comic style. The few in-depth character studies which occur, such as Danny – The Tunnel King (Charles Bronson) and his claustrophobia [and PTSD] are essentially secondary to the heroic escape.

The characters represent the desire to escape as an act of selflessness to achieve the greater good. As with The Dambusters, the stories mostly centre on the actions of officers. The neglect of lower ranks continues a common theme of films in this era though The Great Escape shows a noticeable difference in the way that German characters are represented. The Luftwaffe characters in command of the camp are portrayed sympathetically unlike the SS or Gestapo, a distinction between the representatives of sinister Nazism rather than ‘ordinary’ Germans.

There is grudging respect between opposing Air Force officers but a feeling of utter contempt towards the SS and Gestapo. In earlier films, all German characters are generally portrayed as the same contemptible enemy. Like The Longest Day, the film reflects a new attitude with filmmakers no longer depicting all German characters as inherently evil Nazis.

The inmates eventually escape en masse, and the film develops into a classic British glorious defeat. The escape is discovered before all have got through the tunnel. The majority of those who escaped through the tunnel are eventually recaptured and a few are returned to the camp while the rest are executed.

Pearl Handled Revolvers

Pearl-handled revolvers, riding britches, a highly polished helmet and the odd swear word were just some facets of George S. Patton’s persona. Nicknamed, ‘Old Blood and Guts’ he was respected and admired by friend and foe alike, even though one of the soldiers who served under him, Eugene W Luciano, named his memoir after a line from the film, (As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases) ‘Our Blood and His Guts: Memoirs of one of General Patton’s combat soldiers.’

The screenplay for this film, written by Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North, was based on two books: Ladislas Farago’s Patton: Ordeal and Triumph and General Omar Bradley’s memoir, A Soldiers Story. Bradley was also an advisor for the film. As far as telling the story as it was written, this film does a good job.

Patton 1970

Though the Great Escape was a particularly famous failure, Patton considers a highly successful American officer, George S. Patton (George C. Scott). The film is significant because it dramatically highlights the continued effects of politics on the film industry and how it occurs on several different levels. It shows that, even at the end of the 1960s, war films continued to be used as a positive propaganda tool. In this way, Patton replicates the similar premise behind Lawrence Oliver’s production of Henry V in 1944.

It utilises a successful conflict and commander to boost the low morale of America because of its [not so successful] involvement in Vietnam. The film is remarkable because it hardly considers the real enemy of the conflict, Germany, at all; most of Patton’s hatred is aimed at the Communist Soviet Union and communism in general. The choice of producing a biopic of Patton at this time was particularly inspired, as his hatred of the Soviets and Communism was renowned.

Iconic opening scene

The film begins with Patton’s arrival at a new divisional command in the North African desert in the winter of 1942 and continues to the end of hostilities in Europe in 1945. It deals with his life during the campaigns in North Africa, Sicily, France, and the Ardennes, including such low points as when he was removed from command due to striking a shell-shocked soldier. The film follows the enigmatic, forthright, and arrogant Patton as he fights the Germans, his superiors and his nemesis, Field Marshall, Sir Bernard Law Montgomery (Michael Bates).

The opening scene, Patton’s speech to his assembled troops, highlights the film as a piece of propaganda. The giant Stars and Stripes draped behind him as he speaks dwarfs Patton, resplendent in uniform and pearl-handled revolvers. The speech is aimed not at the assembled troops but rather at the audience, an American public reeling from the after-effects of the 1969 Tet Offensive and the decline in feelings of US Military invincibility, student unrest and racial tensions. Domestically, America was in turmoil and Patton’s speech is reminiscent of a typical Shakespearian-inspired wartime speech by Churchill:

“Americans play to win all the time. That’s why Americans have never lost and will never lose a war because the very thought of losing is hateful to Americans. Now an army is a team, it lives, eats, sleeps, and fights as a team. This individuality stuff is a bunch of crap.”

The Vietnam Effect

The rhetoric attempts to refute Walter Cronkite’s news report from the grounds of the Saigon Embassy where he claimed that America had lost the war in Vietnam. This cynical attempt to portray a heroic war had become wearisome to a nation daily witnessing the horrors of a real war on television.

The inclusion of the striking incident is significant here because it represents the fact that no matter how bad a situation becomes it is still possible for the determined to achieve success as Patton eventually did. This message, though portrayed more subtly than in the Green Berets produced at around the same time, comes more convincingly in Patton because it is based on a real character.

Patton is also significant because it shows elements of progression towards more realistic dialogue with Patton’s speech uncensored [allegedly – depending on which sources you read] including the words ‘goddam’ and ‘crap’, the type of language that had been condemned three years before by the film censor.

However, the film maintains several themes that reflect the earlier period of films discussed. For example, the plight of the private soldier is all but ignored as the focus rests on the general. This imbalance is compounded since Patton placed his quest for personal glory above the well-being of his men. This situation is highlighted by his competition with Montgomery over who would seize Palermo first and observations made by General Omar Bradley (Karl Madden).

Omar Bradley’s view

Though the fact that he was an advisor throughout the film, Bradley is the voice of reason acting as Patton’s conscience. The film attempts to be more sophisticated than typical propaganda films.  During Patton’s attacks on Sicily, many of Patton’s men were killed but he insisted that the attack continued regardless of losses. At this point in the film, Bradley reminds Patton that: “The ordinary combat soldier doesn’t share in your dreams of glory, he’s stuck here. He’s stuck living out every day, day to day with death tugging at his elbow.” This highlights that even in the late 1960s, attitudes were changing.

During Patton’s attacks on Sicily, many of Patton’s men were killed but he insisted that the attack continued regardless of losses. At this point in the film, Bradley reminds Patton that: “The ordinary combat soldier doesn’t share in your dreams of glory, he’s stuck here. He’s stuck living out every day, day to day with death tugging at his elbow.” This highlights that even in the late 1960s, attitudes were changing.

Though strongly influenced by pro-war propaganda, the film does not exclusively deal with such propaganda. Bradley’s character infuses an anti-war element to a degree but also highlights the plight of the common soldier, which is a point of view more representative of the latter era of films under consideration here.

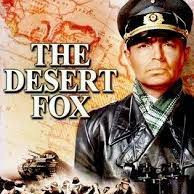

The Erwin Rommel Film (xi)

There is only a short introduction to this section as it is hopefully self-explanatory. This is the first part of two parts with The Erwin Rommel film The Desert Fox (based on the book, Rommel: The Desert Fox by Brigadier Desmond Young) being the first and The Enemy Below being the second.

Anomalies

There are two distinct themes developed in the first selection of films. The first is that even when a film’s main characters are German, as in The 49th Parallel, they are never treated as heroes while their Allied counterparts are always so represented.

The second is that the films generally portray only the glorious aspects of war in the need to stand up to German tyranny. In this way, they are decidedly pro-war. The following two films are therefore notable because they diverge from these two themes. 1951’s Desert Fox attempts to portray a German as a hero, while 1957’s The Enemy Below takes a significant anti-war stance.

The Desert Fox 1951

The Desert Fox, the nickname for Field Marshall Erwin Rommel is a film which portrays Rommel (James Mason) as a hero. The film follows the period of his life in the North African desert just before his first major defeat at El Alamein in 1942 through to his death. At El Alamein, Montgomery’s Desert Rats defeated Rommel’s previously formidable Africa Corps. His absence at the end of the battle due to illness, however, enables him to preserve his reputation.

The film follows the period of his life in the North African desert just before his first major defeat at El Alamein in 1942 through to his death. At El Alamein, Montgomery’s Desert Rats defeated Rommel’s previously formidable Africa Corps. His absence at the end of the battle due to illness, however, enables him to preserve his reputation.

Rommel is finding it increasingly difficult to command his troops in a militarily sensible way because Hitler is exerting ever more personal control over battles; this problem is exacerbated as Hitler becomes more and more irrational. Then in July 1944, he was implicated with those who attempted to kill Hitler in the July Bomb Plot. Rommel is charged with treason. Honourable to the end, he agrees to sacrifice his life so that the lives of his wife and son would be spared, an option not given to other conspirators in the plot.

The Man, The Myth

Unlike, 49th Parallel, where the German characters are represented as the epitome of Nazi evil, the character of Rommel in The Desert Fox is treated more favourably. The film portrays how he is widely respected by the Allies he fought, a fact re-iterated by the film’s narrator, Lieutenant Colonel Young (as himself) when he sees Rommel for the first time after his capture:

“Already a legend in the desert. He was a fox who has chased his hunters back and forth across North Africa as often as they had chased him; his tricks and turns had made even the Tommies chuckle, which is scarcely the proper reflex to the enemy in time of war. Despite which, he was still of course my enemy. The enemy, not only of my country and the army in which I served but of all life as I knew it. Not only of democracy as free men had fashioned it, but civilization itself.”

The film shows Rommel adhering to the rules of war, which were often ignored by his compatriots, this fact created a grudging respect among his enemies that remained until his death, though he was tainted by the regime in which he served.

He is not treated as a hero in this film but as a human character rather than the typical war-loving, cruel Nazi monster. He is also depicted as a loving husband and father bound by duty through his position as a German officer forcing him to follow his country’s leadership whatever their political persuasion because, as he says, he is, “a soldier, not a politician.”

To lessen his hero status, the film only mentions his previous victories fleetingly while focusing on his defeat by Montgomery in October 1942, which begins a chain of defeats culminating in his inability to stop the Allies on D-Day.

It’s not all new

His subsequent execution for a crime he did not commit continues a trend begun in earlier war films where German characters, no matter how sympathetically treated, ultimately end up being killed or defeated.

In order to maintain the sympathetic treatment of Rommel’s character, this film has represented him as a character increasingly disillusioned with Hitler. He is convinced that the ridiculous orders he receives from Berlin are not from Hitler but from the men that surround him. In this way, he constantly defends orders such as fighting to the last man, for example:

“I know it’s not him I tell you, it’s those…it’s those hoodlums again. Those thieves and crooks and murderers. Those…those toy soldiers, those dummy generals with those books and charts and pointers. How can he listen to those non-entities? How can he even stand to be in the smell of such filth? Why doesn’t he slaughter the lot of them and use his own intelligence?”

This disillusionment is made complete when Rommel meets Hitler at his headquarters and sees the gesticulating, raving character that appears in numerous 1940s newsreels. He does nothing more than insult Rommel.

Though the film attempts a different approach to the other films of the period, other factors place it within this period. One such factor is the unrealistic choreographed movements of the shot commandos as they attempt to assassinate Rommel at the beginning of the film. This lack of realism is exaggerated by English accents and phraseology that German characters adopt throughout the film such as when Field Marshall Rundstedt addresses Rommel as “Dear chap.”

In most cases, the action is either viewed from afar, such as bombs being dropped from high altitude or is only alluded to in the film. Again, it should be noted that the plight of the common soldier is ignored because the film is exclusively dealing with the Field Marshall. This film remains significant because it is the first film to deal with a German officer in the lead role, something not repeated since.

The Enemy Below 1957

The next film, The Enemy Below from 1957 goes much further than The Desert Fox which makes it more like the latter films considered here. This film follows the story of two naval crews, one German, in a U Boat, and the other American, in a destroyer escort. The film concentrates on both crews simultaneously and both are equally important to the story.

The American crew’s mission is to destroy U-Boats while the crew of the U-Boat are attempting to meet another German ship, Raider M, so they can pick up a captured code book and return it to Germany.

German characters in previous films were generally dutiful officers, many indelibly tainted with Nazism, but this is not the case here. Von Stolberg (Curt Jurgens), the U-boat captain, makes his disillusionment clear when he tells his second officer:

“In forty-eight hours, we rendezvous with Raider M. We take the captured British code book, and we go home with it. And this is the important thing, not the code book, but when we have it, we go home.”

In this way, he voices a similar opinion to Captain Miller in Saving Private Ryan. The mission that he must undertake is his means to achieve his personal mission, the end of which is his return home and survival.

The growing respect

The German crew are experienced veterans. Lieutenant Commander Murrell (Robert Mitchum) commands the American ship and is also hardened to combat after seeing his wife killed on his merchant ship when it was torpedoed. The rest of the crew are initially naïve and as a result, are arrogantly confident in their ability to sink the German U-Boat.

Another similarity that this film holds with Saving Private Ryan is that Murrell and most of his crew were civilians prior to the war; a fact alluded to several times when the ship’s doctor and Murrell reminisce on their previous lives.

The film is bleak, after losing his wife in such a terrible way, Murrell sees the hopelessness of humanity, a fact he reveals in one of his conversations with the doctor:

“We’ve learnt a hard truth,” Muller says.

“How do you mean?” replies the doctor.

“There’s no end to the misery and destruction. You cut the head off a snake, and it grows another one, you cut that one off and you find another one. You cut that one off and you find another one. You can’t kill it because it’s something within ourselves. You can call it the enemy if you want but it’s part of us, we’re all men.”

Cut from the same cloth

The perspectives of both captains are similarly bleak on the war and life in general. Though Murrell says he does not, “want to know the captain [he is] trying to destroy.” It becomes clearer, as the film progresses, that they are kindred spirits. Both captains gradually come to respect each other to the extent that Murrell risks his life to save the life of his worthy adversary. This scene symbolizes the message of the film, that both sides should really help each other rather than attempt to destroy each other.

The Enemy Below therefore adopts an anti-war stance in a period when the majority, if not all Second World War films promoted a pro-war stance that glorified the pursuit of war. It is these themes depicted here, as uncharacteristic of the earlier period, that will dominate the later period of films considered here.

The Enemy Below 1957

The next film, The Enemy Below from 1957 goes much further than The Desert Fox which makes it more like the latter films considered here. This film follows the story of two naval crews, one German, in a U Boat, and the other American, in a destroyer escort. The film concentrates on both crews simultaneously and both are equally important to the story.

The American crew’s mission is to destroy U-Boats while the crew of the U-Boat are attempting to meet another German ship, Raider M, so they can pick up a captured code book and return it to Germany.

German characters in previous films were generally dutiful officers, many indelibly tainted with Nazism, but this is not the case here. Von Stolberg (Curt Jurgens), the U-boat captain, makes his disillusionment clear when he tells his second officer:

“In forty-eight hours, we rendezvous with Raider M. We take the captured British code book, and we go home with it. And this is the important thing, not the code book, but when we have it, we go home.”

In this way, he voices a similar opinion to Captain Miller in Saving Private Ryan. The mission that he must undertake is his means to achieve his personal mission, the end of which is his return home and survival.

The growing respect

The German crew are experienced veterans. Lieutenant Commander Murrell (Robert Mitchum) commands the American ship and is also hardened to combat after seeing his wife killed on his merchant ship when it was torpedoed. The rest of the crew are initially naïve and as a result, are arrogantly confident in their ability to sink the German U-Boat.

Another similarity that this film holds with Saving Private Ryan is that Murrell and most of his crew were civilians prior to the war; a fact alluded to several times when the ship’s doctor and Murrell reminisce on their previous lives.

The film is bleak, after losing his wife in such a terrible way, Murrell sees the hopelessness of humanity, a fact he reveals in one of his conversations with the doctor:

“We’ve learnt a hard truth,” Muller says.

“How do you mean?” replies the doctor.

“There’s no end to the misery and destruction. You cut the head off a snake, and it grows another one, you cut that one off and you find another one. You cut that one off and you find another one. You can’t kill it because it’s something within ourselves. You can call it the enemy if you want but it’s part of us, we’re all men.”

Cut from the same cloth

The perspectives of both captains are similarly bleak on the war and life in general. Though Murrell says he does not, “want to know the captain [he is] trying to destroy.” It becomes clearer, as the film progresses, that they are kindred spirits. Both captains gradually come to respect each other to the extent that Murrell risks his life to save the life of his worthy adversary. This scene symbolizes the message of the film, that both sides should really help each other rather than attempt to destroy each other.

The Enemy Below therefore adopts an anti-war stance in a period when the majority, if not all Second World War films promoted a pro-war stance that glorified the pursuit of war. It is these themes depicted here, as uncharacteristic of the earlier period, that will dominate the later period of films considered here.

Cross of Iron – 1977

Cross of Iron is the second film of this study to have German lead characters but is remarkably different from its predecessor, The 49th Parallel. Set around the German retreats from the Taman Peninsular during 1942, the film considers the multiple hardships of fighting on the Eastern Front through the eyes of Corporal Steiner (James Coburn), who is later promoted to sergeant, and his close-knit platoon.

The problems for the platoon are exacerbated with the arrival of Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell), an aristocratic officer whose only desire is to earn the Iron Cross. On meeting his new superiors for the first time he encounters their disillusioned bemusement at his desire for service on the Eastern Front.

“Colonel, I would like to make something quite clear… I volunteered for this campaign because I felt that men of quality were needed here. It is time to dispel the myth of Russian invincibility.” Captain Stransky tells them.

“Just how do we do that?” Demands Colonel Brandt.

“Bolstering morale, punishing those who are insubordinate and rebellious. Instilling new respect for ranking officers.”

“Low morale goes hand in hand with defeat after defeat followed by impending defeat. Now you are new to our Russian Front, so I don’t blame you for talking like an… ass.” (This gets a rumble of laughter from the assembled officers, which is cut short by an explosion.

“Of course, I’m not familiar with the Russian Front yet. But I firmly don’t believe that the ideas of the German soldier…”

Brandt harshly interrupts him:

“The German soldier no longer has any ideas! He’s not fighting for the culture of the West… not for one government that he wants: not for the stinking party, he’s fighting for his life. God bless him!”

“Well Sir, I’m a soldier and as a soldier, I think it is my duty to subordinate my ideas to the principles of my country, right or wrong.”

It is this dialogue, at the beginning of the film, that sets the scene for Stransky being the naïve idealist among the jaded veterans of the campaign. His aristocratic heritage forces him to follow ideas of patriotism and his desire for the Iron Cross. He is not a Nazi but is obliged by coincidence to ally himself with Nazi ideals. From the outset, his opinions run against the apathy of his superiors and the insubordination of his antithesis Steiner.

Stransky’s cowering reaction to the explosion in the command bunker reveals his deeper personality more than any of his rhetorical bravado. He is a glory-seeking inexperienced officer who is a coward. The irony goes deeper since characters like Steiner and Brandt are skilled in warfare and have earned the Iron Cross, not through what they regard as acts of bravery but through acts of survival.

Except for Stransky, it is this need for personal survival through the war of annihilation on the Eastern Front that is of paramount importance to Steiner and the rest of his comrades. Steiner’s’ chances of survival, and those of his men, are put in jeopardy with the arrival of Stransky, who is prepared to risk the lives of others rather than his own.

The problem of Stransky’s cowardice is exposed during the first Russian attack when he claims credit for leading the counterattack, an action designed to earn him the Iron Cross, though, in fact, he was cowering in a bunker.

Lieutenant Meyer, one of Steiner’s comrades, instigated the counterattack but lost his life whilst Steiner himself was injured. Stransky requires testimony from two witnesses; he bribes his adjutant, Lieutenant Trebig, by threatening to disclose his homosexuality and is relying on Steiner’s support. Steiner retorts that he does not believe that Stransky deserves the Iron Cross and when he is called to give testimony, he is reticent to do so.

Lieutenant Meyer, one of Steiner’s comrades, instigated the counterattack but lost his life whilst Steiner himself was injured. Stransky requires testimony from two witnesses; he bribes his adjutant, Lieutenant Trebig, by threatening to disclose his homosexuality and is relying on Steiner’s support. Steiner retorts that he does not believe that Stransky deserves the Iron Cross and when he is called to give testimony, he is reticent to do so.

Cross of Iron contains elements present since the earliest Second World War films. One theme is that war destroys innocence. The film is significant because it is the first film to highlight the young age of people fighting in the war and how their innocence is generally destroyed. This is achieved by the film primarily focusing on the lower echelons of the German Army and specifically the treatment of the young Russian prisoner and Dietz, a new member of Steiner’s squad.

Stransky’s innocence is shattered but the film continues to focus on the young people affected by the war, a factor reiterated during the closing credits. Steiner confronts Stransky and rather than shoot him, he forces him to face a new Russian attack with him. Stransky’s clumsy incompetence makes Steiner burst into hysterical laughter. The laughter continues as the credits begin to roll.

The same patriotic song, sung by boys, from the opening credits, fades but this time the pictures are not of heroic Germany but rather the horrors of the war: civilian hangings, wounded children, and concentration camp inmates. Thus, the anti-war sentiments throughout make Cross of Iron particularly bleak, sentiments which are to a certain extent, replicated in the following film.

The Big Red One 1980

“The Big Red One is a powerful, humorous, and touching autobiographical film that’s the last of the great World War II movies… Fuller manages to create one of the most poignant films ever made. Fuller demonstrates his philosophy that, ‘the only glory is surviving.’

By focusing on the Four Horsemen and through a series of searing scenes filled with unforgettable images (a Nazi hiding behind a crucifix in the middle of the battlefield; terrified eyes of concentration camp prisoners) … Vehemently anti-militaristic, the film celebrates camaraderie and brotherhood and eloquently demonstrates the ultimate futility of war.”

The film follows a small group of naïve soldiers led by The Sergeant (Lee Marvin) a First World War veteran. The four survivors of their first battles, the invasion of North Africa and the defeat at Kasserine Pass become veterans themselves and are nicknamed the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

From North Africa, the film follows them and a stream of anonymous replacements to Sicily, Italy, the D-Day landings, the fighting through France and the Low Countries, and Germany itself. The story ends with their discovery of the horrors of the Holocaust in the Falkenhau concentration camp.

The Seventh Virgin Film Guide states that The Big Red One was both, “the last of the great World War II movies,” and that it was, vehemently anti-militaristic,” by demonstrating the “futility of war,” contradicts itself because the guide compares this film against movies produced in the earlier period considered in this study. It was this period, more than any other glorifies the pursuit of war rather than this film where war is not glorified. However, the guide does highlight several pertinent points of interest.

The key here is that The Big Red One is anti-war in nature. The characters, especially the narrator, Private Vinci (Bobby Di Cicco) and the Sergeant constantly stress their anti-war beliefs and the bleakness of human conflict. One such example is when the squad is crossing the French battlefield and comes across a cenotaph. A new replacement remarks.

“Would you look at that, they put up the names of all our guys that got killed.”

“That’s a World War I memorial.” The Sergeant answers.

“But the names are the same.”

“They always are.” The Sergeant replies.”

At this point, the Sergeant is particularly affected by the futility of war because they are crossing the same French battlefield that he fought over in the last days of the First World War. It was here that he killed a surrendering German after the armistice.

His inner turmoil about this killing which he classes as murder is brought up in the final minutes when he is again confronted by a surrendering German, unaware that the war has already ended. He attacks the soldier and thinking he has killed him, leaves him. The remaining Horsemen discover him still alive and revive him. Vinci, the narrator, again pinpoints the central theme of the film:

“Saving that Kraut was the final joke of the whole goddamned war. I mean, we had more in common with him than with all our replacements who got killed, whose names we never even knew. We’ve all made it through, we’re alive. I’m going to dedicate my book to all those that shot but didn’t get shot because it’s about the survivors. Surviving is the only glory in war if you know what I mean.”

The proposed dedication is significant because many earlier dedications were exclusively aimed at Allied soldiers, whereas this is aimed at all who had survived. This is a theme also adopted with the dedication for Memphis Belle in 1990.

In this way, the film continues the theme of more sympathetic treatment of German soldiers, with a clear distinction made between the ordinary German soldier and the concentration camp guards. This attempts to show that individual soldiers on both sides had similar doubts, a fact elaborated on when the subject of murder arises. Griff (Mark Hamill) tells the Sergeant:

“I can’t murder anybody.”

“We don’t murder, we kill.” The Sergeant replies.

“It’s the same thing.”

“To hell it is Griff! You don’t murder animals, you kill them.”

In the subsequent scene in the German camp, the same discussion arises.

“In Libya, I saw him [Schroeder] (Siegfried Rauch) murder a German officer.” Private Gerd says.

“I did not murder him. I killed him when he ran from a fight with the British.” Schroeder replies.

“Murder, kill, it’s the same thing.”

“We don’t murder the enemy, we kill them.”

Even though the characters from both sides arrive at similar conclusions in an argument about the justness of war, a similar distinction is made between the fanatical Nazis and the ordinary Germans as was made in The Great Escape.

The fanatical Nazis are evil whereas anyone who disagrees with the Nazis is their enemy, a point made when Schroeder shoots Gerd immediately after the dialogue given above because he has ridiculed the Nazis and refused to fight. Therefore, this film does not go as far as Cross of Iron in its treatment of German characters, it is the Nazi character, Schroeder, that follows the Four Horsemen wherever they go.

By adopting an anti-war stance that does not glorify the war, Fuller has tentatively been able to include the Holocaust in the final segment of the film. Here, the film is at its most gritty as it deals with the contentiousness of the Holocaust through the visible anguish that all the characters suffer.

Elsewhere, the film fails to convey any great feeling of reality, especially during combat. This is mainly due to the almost slapstick appearance of bullets striking objects, as, during the North African invasion, bullets appear as small puffs of sand as they strike. More noticeably this occurs during the attack on a monastery when one of the mentally ill patients grabs a weapon and fires into the crowded dining room with bullets causing no more damage than destroying a few bits of crockery.

The constant movement of the squad between different countries creates a piecemeal story that further underlines the unrealistic nature of the film.

The Big Red One includes a great deal of interaction between principal characters, a theme not always common in earlier war films. The story was an autobiography of a private soldier with most dialogues occurring between a few squad members.

One seldom sees the vast numbers involved in a battle, which generates a lack of grandeur. Saving Private Ryan also focused on a small squad but conveyed a feeling of grandeur with the characters being part of a much larger event.

The local interaction between lower-ranking soldiers and their desire for personal survival are features that set this film within the characteristics of later Second World War films. Unfortunately, however, the comedy in some scenes combined with the lack of scale draws attention away from the serious anti-war message the film is attempting to portray. In this way, the film does not appear as emotionally bleak as either Cross of Iron or Schindler’s List.

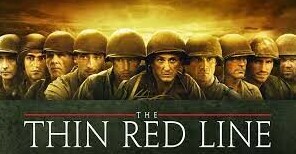

Memphis Bell

After The Big Red One, there was a gap of ten years until the next major Second World War films were produced. This reflected the deluge of Vietnam films and the development of action movies during this period. It also represents the waning fortunes of the British film industry and Hollywood’s rise to almost complete dominance. Only Hollywood at this time could finance films that matched the spectacle of action movies.

This development of films aimed at the lowest common denominator of movie audiences proved detrimental to profound themes examined in the context of Second World War feature films. This coupled with the Vietnam War as a subject, meant there was no major film on the Second World War until Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun in 1987, a film set in the East and therefore not considered here. However, in 1990, Memphis Belle showed that many stories from the Second World War had yet to appear on the big screen.

Lucky?