This was the only film for this study which was viewed in the way it was intended, on the big screen. I saw Saving Private Ryan within days of its release in 1998. It was amazing and exhausting in equal measures, particularly the first twenty minutes or so. In conjunction with a lecture on the representation of warfare in film, this viewing was the inspiration for writing about Second World War films in a thesis for a Masters. So here’s my Saving Private Ryan movie review.

By coming in at not far shy of two thousand words I can now appreciate far more why some other films, particularly A Bridge Too Far had so little written about them in this study.

Saving Private Ryan

1998’s Saving Private Ryan is the most recent film in this study. Produced and directed by Steven Spielberg, it utilises the director of photography, Janusz Kaminski, and other members of the production team from his earlier Second World War Epic, Schindler’s List. This film depicts events around the D-Day landings on Omaha Beach in early June 1944. The story focuses on a squad of American soldiers led by Captain Miller (Tom Hanks).

The story has three distinct parts. The first section considers an old man, identified as a veteran of the 101sth Airborne Division (he is wearing a pin badge which is small and may not be noticed by some/many of the audience), as he visits a vast military graveyard in Normandy.

This contemporary segment sandwiches the rest of the film, which appears in flashback. The second section is a graphic recreation of the Omaha Beach assault, and the final section is the mission to save Ryan.

Omaha Beach

The initial graveyard scene unfolds into a landing craft approaching Omaha Beach on the 6th of June 1944. And it appears through the old man’s memory. However, it is not, in fact, his reminisces but the beginning of the main story, a fact clarified when the concluding graveyard scene reveals the veteran as the Private Ryan of the title.

Leonard Matlin describes Saving Private Ryan as:

“a genuinely complex examination of heroism in the field…[containing] the most realistic and relentlessly harrowing battlefield footage ever committed to fiction film.”

Realism

It is during the invasion scene that many of these points are developed. The battle scenes throughout the film are very realistic. Spielberg has used technology [and other techniques] to create as much realism as possible. This, in conjunction with period-type filming and clever use of camera lenses, allows the audience to almost become one of the characters. This is most noticeable when soldiers jump over the sides of the landing craft to escape the maelstrom of bullets. The camera takes the point of view of Captain Miller as he is first, submerged, then witnesses bullets entering the water and striking soldiers around him, and then as he eventually surfaces and scrambles onto the beach.

Once on the beach, he is concussed by an explosion, the sounds of the film become momentarily muted, and the action slows down as he is recovering. Eventually, the shouts of the panicked men around him break him from his stupor and he begins to try and reorganise the assault.

Later, as his squad is attempting to get off the beach, the bullets appear to come directly at the camera (visible by the phosphorescent tracers on the bullets themselves) and the strike a point where the camera has just been. Further careful use of sound also provides a definite and more realistic crack as bullets are fired and thump as the bullets pass the camera or impact someone or something.

The Mission

The “complex examination of heroism in the field,” is central to the story after the beach has been captured [and arguably during the invasion]. Having survived the invasion and battles that immediately followed it, Captain Miller’s squad is ordered to go behind enemy lines to rescue Private James Ryan who, since his three older brothers were killed in action, is to be sent home.

The squad, on receiving this news, are incredulous rather than stoical, a reaction that would not have occurred in earlier films. The squad are not afraid to voice their opinions, but Miller is more reticent and adopts a position of distance and command. He refuses to divulge his thoughts to his men, even when asked directly by Private Reiben (Edward Burns):

“So, Captain, what about you, I mean, you don’t gripe at all?”

“I don’t gripe to your Reiben, I’m a Captain, there’s a chain of command, gripes go up, not down, always up. I gripe to my senior officer and so on and so on and so on. I don’t gripe to you; I don’t gripe in front of you. You should know that you’re a Ranger.”

“I’m sorry sir, but um, let’s say you weren’t a Caption or maybe I was a Major, what would you say then?”

“Well, in that case, I’d say, this is an excellent mission, Sir with an extremely valuable objective Sir, worthy of my best effort Sir. Moreover, I feel heartfelt sorrow for the mother of Private James Ryan, and I am willing to lay down my life, and the lives of my men, especially you Reiben, to ease her suffering.”

This sarcastic reply takes the form of a fatherly reprimand stopping the discussion amongst the squad.

Mutinous Thoughts

The feelings of unfairness felt by the squad, sacrificing their eight lives for the life of a stranger deepens as one by one the squad members die. Miller’s position is eroded as he cannot provide convincing answers to their ever more demanding questions. It is Miller’s leadership and calmness under pressure that kept the squad together on Omaha Beach and in the subsequent battles, increasingly stressed, his squad become ever more mutinous. His position is even more strenuous because he is asking himself the same questions and cannot find adequate answers.

Gradually Miller reveals feelings about the mission to Sergeant Mike Horvath (Tom Sizemore). His feelings eventually surface when the squad attacks a radar station where Wade (Giovanni Ribsi) is killed. The squad want to kill the remaining German soldier, but Miller lets him go. Reiben is furious and wants to desert while Horvath is ready to shoot him. Miller appears to lose control, ignoring all that is going on. Corporal Upham (Jeremy Davies) begs him to do something, and he replies:

“What’s the pool on me up to?”

“What?” Upham incredulously replies.

“Mike, what’s the pool on me up to right now? What’s it up to? Is it $300, is that it, $300… I’m a schoolteacher… I teach English composition in this little town called Addley Pennsylvania. The last eleven years I’ve been at Thomas Alva Edison High School. I coach basketball in the springtime.”

“Well, I’ll be doggone.” Horvath whispers.

“Back home, when I tell people what I do for a living, they think, well, that figures. But over here it’s a big, big mystery. So, I guess I’ve changed some. Sometimes I wonder if I’ve changed so much my wife is even going to recognise me when I get back to her, and how am I ever going to tell her about days like today?

Ah, Ryan, I don’t know anything about Ryan. I don’t care. The man means nothing to me; it’s just a name. But if you know… if going to Ramelle and finding him so he can go home. If that earns me the right to get back to my wife, then that’s my mission… I just know that every man I kill, the farther away from home I feel.”

Bringing it all back together

Through this revelation, Miller brings his squad back together. He revealed his humanity when his squad was beginning to lose theirs and removed the mystery that surrounded him. The inner turmoil Miller is suffering between his duty to follow orders and his desire to remain decent and honourable to himself breaks the surface with his humanity prevailing. In this way, Saving Private Ryan continues the trend of most other films of this period by considering the deep effects that this great human conflict had on ordinary people, both military and civilian, who fought it. Miller did not attack the radar station because it was his military duty to do so but rather because it was his moral responsibility. He could not cope with the knowledge that other Americans would have been killed if he left it, unfortunately, his plan backfires when Wade is killed but he is unable to emotionally warrant the execution of a German soldier in retribution.

The strength of fraternity forged in battle is highlighted when Corporal Upham joins the squad as an interpreter. He is the outsider treated with disdain. He is only reluctantly accepted when Ryan is eventually found, and he has experienced some realities of war. His battlefield experience brought nothing but danger to the squad.

Ryan is found

The discovery of Ryan and his refusal to desert, “the only brothers I have left,” changes the squad’s anger into grudging respect.

To ensure greater authenticity Spielberg went to extraordinary lengths, sending actors to ‘boot camp’ where they had to endure basic training [Matt Damon did not have to do it with the others to create real disdain for his character]. This attention to detail translates through their performances.

Educational Intentions

This film attempts to educate, and Tom Hanks said the film was specifically aimed at a young audience, an audience who consider the Second World War to be, “ancient history.” He continues:

“We don’t want to lecture an audience. We are trying to communicate to them that mere mortals, people the same age as themselves had to be called upon to make this hard sacrifice in service of mankind.”

Empire of the Sun, Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan have all promoted similar ideals by concentrating on ordinary people, be they children, a civilian population, or civilian soldiers. The film shows through the Ryan character that people who suffered these sacrifices are still alive and are therefore not ancient history. He utilised a similar method in Schindler’s List when the Jews leave the factory when the war ends to cross over the hill into the next town. As they cross the hill, the black-and-white photography changes to colour as the survivors themselves replace the actors.

There are other factors in this film that continue the trends of the latter era. One is the inclusion of a Jewish character that taunts passing German Prisoners of War with the chant, “Juden, Juden, Juden,” at the same time as showing them his Cross of David. This scene is reminiscent of another scene in Schindler’s List when a young German girl taunts the Jews as they are going to the camp for the first time.

It’s not all good

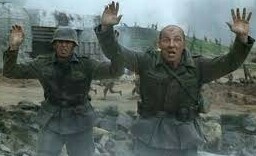

Scenes admitting American troops committed acts of atrocity also appear in the movie. Firstly, two American soldiers shoot two Germans [actually Czechs], just after they have raised their hands in surrender during the capture of the cliff-top positions above Omaha Beach.

The second is when there is an angry debate on whether the captured German machine gunner at the radar station should be executed. Alluding to such actions re-iterates the fact that most of those fighting were relatively young and were facing great moral dilemmas.

This subsequently raises the central dilemma of the film concerning Miller’s attempts to remain decent, a dilemma that ends ironically and tragically when having done the decent thing by releasing the German, the same German subsequently kills Miller. This represents the moral question of whether it is possible to remain honourable and decent in the extreme situations encountered in war.

Saving Private Ryan, by rejecting the cool-headed hero characterisations of the 1940s and 1950s and replacing them with more realistic and confused individuals is saying that it is extremely difficult to remain decent and that it does not matter because the killing is indiscriminate and ignores the moral values of the victims. Therefore, the war in war films is no longer a heroic endeavour perpetrated by heroes but rather an endeavour perpetrated by ordinary individuals who react to extraordinary situations that make them reluctant or tragic heroes.

And there’s more

This analysis goes to show that the process of choosing films was highly selective so points could be proved with the films. In this section, the earlier period of films is characterised by a failure to consider the psychological effects of war on the characters, films such as 1958’s Ice Cold in Alex do just this.

There are stories about veterans seeing this film and being triggered by the realism of the effects, especially in the Omaha Beach sequence. In addition to the techniques mentioned here to create as realistic an experience as possible on the screen, there is an almost endless list of others. Spielberg used amputees in scenes where soldiers lost limbs and used Irish Army soldiers as extras. Interestingly there were also parts of the Omaha sequence where the cameraman was not told which direction to film but just to film whilst going up the beach, in this way, some of the reactions are real reactions to what is occurring all around them. However, the TV show Myth Busters proved that bullets do not actually travel through water in the way they do in the film and lose energy quickly so are unlikely to have struck soldiers underwater in the way they do in the film.

I will soon publish a blog about Spielberg’s and Hanks’ influence on the Second World War genre of filmmaking.

The final thesis installment is up next folks.

All the best folks

Bigt