Market Garden Musings

A question for the ages is why did September 1944’s Operation Market Garden fail. This is not going to be a definitive answer because I do not think there is one. I do not claim any new knowledge or point of view, but I have studied it in one way or another for thirty years and been aware of it for forty and I want to sort out the options in my head and find that writing them down helps me do this. I may reach a conclusion, but as I often told my history pupils, leave some space at the top of your essay for your introduction as you may change your mind part way through writing what your conclusion is. So here’s my Market Garden summary.

Start at the End

This was probably to do with my own experience of developing my conclusion as I was writing and as an essay introduction is arguably the part of the essay when you write, ‘this is what I’m going to tell you.’ Therefore, if you have not made up your mind before writing the essay then you cannot possibly write your introduction until you’ve written the rest. In hindsight, this could easily be a result of my poor revision planning where I did not necessarily think about which questions I might be asked and so did not prepare my answer in my head.

I’m not claiming to be an expert, but during my many years of study, I have read many books and articles, watched many documentaries, and listened to hours of podcasts when it has been discussed. My interest began with the film A Bridge Too Far. I do not know the minutia of the operation, for example, what was happening where at a particular time on a particular day or in a particular place. I will also undoubtedly miss some things along the way to my conclusion if I make one.

This discussion is pretty much me talking to myself on metaphorical paper but I would love to hear anyone else’s thoughts or things I have missed. I appreciate that some readers will know far more about this than me or at least something but some readers may not, so this will be written explaining who people are as much as possible.

Why The Fascination?

The failure of the operation has been discussed almost since it took place. So why is there a fascination with it and why are more books being written and discussions happening? In my humble opinion, there are two reasons. Firstly, there is probably more fat to chew on with a failure rather than a success. Secondly, the operation occurred in amongst a series of successes which began in June 1944 and continued through to May 1945. There were setbacks during this time, but no failures as obvious as Market Garden.

After explaining that an introduction was: ‘This is what I’m going to tell you,’ I would then say that the main part of the essay is: ‘So this is me telling you.’ So here we go, this is me telling you about who is to blame and maybe some other stuff too:

No Plan survives first contact with the enemy.

Market Garden was the culmination of a series of airborne operations that were cancelled as objectives were captured on the ground. It also took some of its ideas from these plans, such as Operation Comet.

Market was the airborne phase. Three airborne divisions would be dropped to seize a series of bridges.

Garden was the armoured thrust by XXX Corps to relieve the airborne forces. It was envisioned that it could take as little as two days and no more than four to reach the northernmost bridges at Arnhem.

However, as the adage above states, the plan did not survive first contact with the enemy, but the plan was so poor that there was not much chance that it would.

The Plan – a lesson in compromise

Lessons from D-Day were not taken on board, so the 82nd

and 1st Airborne, who had no real coup de main capabilities or plan, were dropped miles away from their objectives. Airborne operations rely on surprise which they achieved to a degree, but this was neutralised by the distances from the objectives. German units could then block these advances relatively easily. The Allies were at the end of two long supply chains, a land-based one from Normandy that culminated in a single highway and an airborne one from the UK which was reliant on the weather. The Germans had shortened their lines as the Allies had extended theirs by retreating to almost their own border. Once it became obvious to the Germans what the objective was, they could then attempt to strangle the 1st Airborne Division by impeding the progress of XXX Corps.

Multiple lifts were necessary.

The fighting power of two of the airborne divisions was severely reduced in two major ways. Firstly, there was insufficient airlift capacity to drop all parts of all the divisions on the first day of the operation, so divisional commanders had to consider their tactical necessities to make the best of the troops they could get in this first drop to capture their objectives. Secondly and inextricably linked, they also needed to defend the landing and drop zones for lifts over the subsequent days.

In the case of the 1st Airborne Division, only about half of the fighting force landed on the first day was sent to the bridges in Arnhem and this was only a proportion of the division anyway. Once in Arnhem, this relatively small force had to capture two bridges and a ferry crossing as well as occupy the town and capture and secure Deelen airfield. A massive area to defend in normal circumstances let alone by lightly armed airborne troops.

So who was to blame for these mistakes before the battle even started?

Start at the Top – Monty

Well, almost, but more of that in a bit. Field Marshall, Sir Bernard Law Montgomery of Alamein must take a big chunk of the blame. He convinced Eisenhower to back the operation on the 10th of September despite Eisenhower’s misgivings about a thrust up a single highway over multiple water obstacles. Monty was under pressure himself, V2s launched from the Netherlands were landing in Britain.

However, this is not the full story. Monty had only recently become a Field Marshall, potentially just to soften the blow of Eisenhower becoming Supreme Allied commander for someone as vainglorious as Monty this would have been a blow indeed. The war was nearly over, the Allies knew that, so he was also fighting for a position at the post-war table that looked like it was being taken away from Britain as the US began to be the dominant force in the fighting in Western Europe.

Monty had developed the plan but there were limitations to what could be achieved. All troops could not be landed on the first lift and most notably in the British case, the drop and landing zones were as far as eight miles from the road bridge at Arnhem. Troops had to be left to defend these zones which could then not be used in the advance through Arnhem to the bridges. There would be further drops on the following two days, weather permitting. The division was also expected to occupy large parts of Arnhem and capture Deelen Airfield so the 52nd (Lowland) Division could be landed on it.

Eisenhower

He placated an angry Monty and agreed to the plan but in a far more limited way than Monty had first demanded.  Eisenhower had a tough job, he was stuck between at least two charismatic generals, Patton and Monty who thought their plan should be the one followed. He was also under pressure from above. The powers that be wanted the newly formed (1st of September 1944) 1st Allied Airborne Army to be used. Airborne training is expensive and having thousands of troops was a waste of money.

Eisenhower had a tough job, he was stuck between at least two charismatic generals, Patton and Monty who thought their plan should be the one followed. He was also under pressure from above. The powers that be wanted the newly formed (1st of September 1944) 1st Allied Airborne Army to be used. Airborne training is expensive and having thousands of troops was a waste of money.

However, he was in command and he agreed to the operation but did not give it the complete backing that Montgomery had demanded.

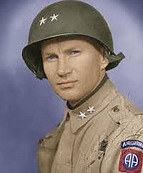

Boy

Lieutenant-General ‘Boy Browning’ was in tactical command of Market, so the British 1st Airborne Division, The US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions the 1st

101st Airborne Divisions the 1st

Independent Polish Parachute Brigade and the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division. However, once in situ, there was very little for him to do on the ground, he just had to leave his divisional commanders to fight their individual battles and capture their bridges. Yet he decided to fly his headquarters in by glider using 32 Horsa gliders that could have been used for other troops or equipment vital to the operation. The whole operation was only meant to last two days. His presence on the ground was therefore superfluous and he could have just as easily advanced on the ground with XXX Corps.

What will follow is a discussion of those generals that Browning was directly commanding and the units that were sent to relieve them.

Taylor

Maxwell Taylor’s 101st Airborne Division was tasked to capture the bridges closest to XXX Corps’ advance, including the Eindhoven Bridge. They did capture four out of five of the bridges relatively easily but the bridge at Son was blown up just as troops advanced upon it. The Bailey Bridge that was built to replace it was completed in ten hours, but these ten hours were over the evening and nighttime of the second day of the operation. XXX Corps had taken much longer to get to Eindhoven than planned.

Gavin

Jumping Jim’s 82nd Airborne Division was tasked with capturing the vital Nijmegen Bridge as well as the Grave and Heuman Bridges. In addition, they were tasked with capturing the Groesbeek heights which dominated the area. Browning had agreed with Gavin that the heights were the vital objective and that the Nijmegen Bridge would be captured when all other objectives had been achieved, but no bridge meant no relief for the 1st Airborne Division. However, the highway could easily be dominated by the Groesbeek Heights and even cut completely so even if the bridge had been captured, XXX would have struggled to get through to Nijmegen.

Bridges. In addition, they were tasked with capturing the Groesbeek heights which dominated the area. Browning had agreed with Gavin that the heights were the vital objective and that the Nijmegen Bridge would be captured when all other objectives had been achieved, but no bridge meant no relief for the 1st Airborne Division. However, the highway could easily be dominated by the Groesbeek Heights and even cut completely so even if the bridge had been captured, XXX would have struggled to get through to Nijmegen.

Urquhart

Had no tactical experience in airborne operations. This is not to say he did not have battlefield experience, but he was used to distinct frontlines and not the situation that airborne troops always find themselves in by being surrounded /the nature of airborne operations which means you are surrounded. However, the distance from the drop and landing zones of at least eight miles made his job difficult, to say the least.

The intricacies of the plan to capture the bridges at Arnhem were down to Urquhart, but he had to make do with the cards he had been dealt. He was not allowed a coup de main force, so he decided to use the 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron to race from the landing zones to the road bridge. This may be Auftragstaktik or directive command, but the directive surely needs to make some sense in the first place and not be severely limited by other factors.

Ultimately the divisional commanders must attempt to make a plan work that was risky and full of holes from the start, so they cannot really be blamed for any subsequent mistakes. The plan was the issue, and those generals and field marshals higher up the chain of command who either came up with the plan or ok’d it that should be blamed.

Unfortunately, as the plan quickly began to unravel, Urquhart went to investigate the holdup and became stranded. He was therefore missing, presumed dead by some for a significant period of time when he should have been directing the advance into Arnhem.

Making Tea

Since the film XXX Corps has been forever tainted with halting their advance after the capture of the Nijmegen Bridge, having a rest, and making tea.

I would suggest that this is somewhat of a chicken and egg situation, when ordered to halt the natural inclination of many a Tommy would be to get a brew on. However, at this point, Frost’s on the Northern end of Arnhem Bridge was pretty much destroyed, and it was not known what opposition was between Nijmegen and Arnhem so a further advance in darkness was fraught with danger. It was not the delay here that lost the battle for Arnhem as this was the fourth day of the battle, it was the delays in the preceding days, both with the advance of XXX Corps and drops on day two and day three that undoubtedly did it for 2 Para at the bridge. These issues are also in conjunction with the necessity to defend landing and drop zones for several days which will be discussed later.

What of the Germans

If you know the film, you’ll probably not be able to think about this line from A Bridge Too Far without hearing the ‘interesting’ accent that Gene Hackman adopted to play the Polish General Sosabowski. The operation proved that the Wehrmacht was not quite kaput just yet.

One of the main reasons they were successful in defeating the operation was the use of the ad hoc formations known as Kampfgruppen. Commanders would gather whatever troops were available, arm them and send them to the battle. Several of these were formed along the axis of the advance and it was often these that met the airborne troops first.

These formations are sometimes described as a sign of weakness of the crumbling Wehrmacht but they proved successful throughout the operation, even if it was just to delay the allies enough to bring more regular formations into the battle.

Final Thoughts – at least for now

Ultimately, Operation Market Garden was not a success, despite what Monty said to the contrary. There was no breakthrough into the Ruhr, and V2s were still being launched as late as 27 March 1945 and the war did not end that Christmas.

Was it worth the punt and did it get the punt it deserved? Yes and no respectively. If the three points above had been achieved then it was definitely worth it but it could have done with far more support than it got. I admit, I am not sure how this could have been done.

All the Best

BigT

Selected books

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases)

A Bridge Too Far – Cornelius Ryan

Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle – Marton Middlebrook

Arnhem 1944 – William F. Buckingham

Arnhem: A Tragedy of Errors – Peter Harclerode

It Never Snows In September – Robert J. Kershaw

Arnhem – Major-General R E Urquhart

Arnhem: The Battle for the Bridges – Antony Beevor

Great wee article sir. I have an original and complete copy of Blake’s ‘Mountain and Flood:History of the 52nd Lowland Division’ if you’d like to borrow it?

Thanks again for reading an article of mine. The book sounds a great borrow. Take it easy.